Ways of showing things, ways of seeing. I was given a Box Brownie camera in the late 1950s and I treasured it. I took the photo below while going upstream in my father’s handbuilt rowboat. It was thrilling and scary. Boats were rowed with heavy wooden oars. Nobody on the river had heard of life-jackets. The light poured down on young skin, burning it even through the clouds. There was almost no settlement then; only our house and one other along the Bar Point foreshore. You can just see the slight clearing at the water’s edge which marked the location of our house.

When I recovered this old photograph a few years ago I wanted to paint an image from it.The slightly choppy waters became the marker of a storm. The still, slightly hazy sky to the north turned into wild clouds. Was this a body-memory of how I felt that day, far out on the river? How different the river feels today: tidy, organised, wharfs and pontoons to land on, clean neat houses. Same mountains in the distance, though. The drone view is not possible from one’s own body, unless one is paragliding or going up to heaven.

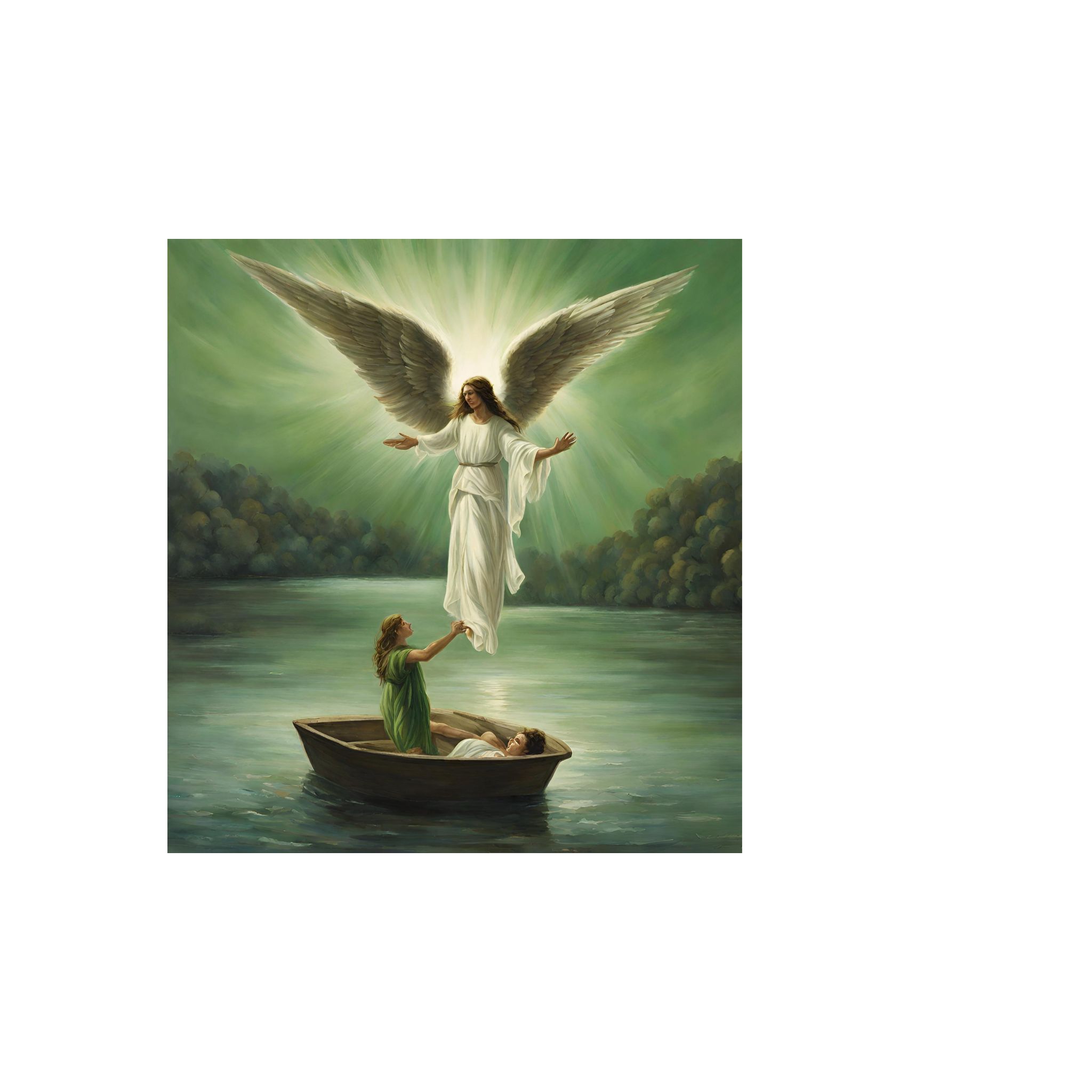

I never paint from someone else’s photographs. The intrigue of the personal relationship remains. Can a photograph provide the basis for a successful painting? There are huge debates about the wisdom of using photographs at all. On the other hand, some artists regard an extreme photo-realism as the hallmark of great picture making. Hyperrealist paintings win prestigous prizes. Now there are AI images which are even more incredible, since they create a hyper-real image of something that exists exactly nowhere. The image below was generated by a few simple words. It could be a photograph, or equally a hyper-real painted image.

Today many artists use photographs as “references” yet produce paintings which look almost nothing like the image. When, in more naive times, I have protested, the answer is always the same: “It is a painting. A painting is not reality”. Their priority is to make “a good painting”, something which has its own laws and logic. But what is the logic of a painting? It can only obey the dictates of its creator, and ultimately these must arise from human concepts of aesthetics, culturally bound and individually determined.

In my own work I struggle along this difficult line. I want to pay tribute to the world I am engaging with, but technical demands seem beyond me. A dark morning with mist and heavy cloud draping the powerful escarpments of the Blue Mountains sets in train a range of possibilities, linking to personal memories of the times I spent in these places, and the struggles which emerge in the paintings themselves. But the paintings develop, the feelings change. What began as a dark expanse keeps on developing highlights and contrasts.

Over and again, many of my painting mentors tell me “do not work from photographs”. Sandra Blackburne (see https://sandrablackburne.com/) demonstrates her method of outdoor sketching first on a large loose scale in charcoal, then in loose swathes of gouache on the spot, then takes her work to the studio, creating large canvases in layers of oils. The pictures did not look anything like each other. Yet they were of the same “scene”.

Sandra’s paintings deeply express their “scene”. They are full of movment and action and light and a sense of easy wilderness.

While appreciating the subtle brilliance of this work, I keep struggling with the feeling that I want the actual place I am painting to “be” there, to exist in its own right, to be a visual experience which another person would recognise and say, “Yes, I know exactly where that is”. This is not to downplay the expression of personal feeling through the mark-making process, which, as it develops, tends to become more and more abstracted. All this has something to do with the specific ethical demand to pay respect to the land and its histories.

I am trying to explore the tradition of Australian landscape painting from its first beginnings to the present. It is a work in progress which hasn’t progressed very far. Some extracts, quotes and observations will be posted here from time to time. I don’t want to write a “history”, but have an increasing conviction that something very interesting is happening between the emerging understanding of country, in a First Nations sense, and the means of expressing that through an emergent sometimes florid quasi-Impressionism. Women artists are at the forefront of this development.